April 2025 / Reading Time: 9 minutes

STUDY G: Unmasking exploitation: Study of Supreme Court cases reveals changing landscape of child sexual exploitation and abuse in the Philippines

Introduction

This study examines the evolution of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) in the Philippines, focusing on cases from 2003 to 2024, particularly those heard by the Supreme Court. The implementation of the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act (Republic Act 9208) in 2003 established legal frameworks to combat trafficking and exploitation. Analysing 56 Supreme Court cases, the study highlights how exploitation methods have evolved, becoming more difficult for authorities to detect and prevent. The findings emphasise the increasing complexity of both online and offline exploitation, stressing the need for stronger legal and social protections for children.

Previously, large, organised syndicates controlled many victims, but now smaller, more covert groups exploit children. These groups are harder to detect as they use discreet methods and exploitation is increasingly occurring within families and close social circles. The locations of abuse have shifted from public venues to private homes and online platforms, where abuse can be livestreamed or recorded. Recruitment tactics have also evolved, with perpetrators using social media to coerce, manipulate and threaten victims. The roles of those involved have blurred, as ‘pimps’ (the term used in Supreme Court cases to describe people who make money by controlling and selling others or sexual services) are now directly abusing children, making detection harder [1].

Urban centres like Manila, Cebu City and Angeles City remain hotspots for CSEC due to tourism, poverty, and the global reach of digital platforms. While law enforcement efforts have improved, the rise of technology-facilitated exploitation has made these crimes more complex. Enhanced legal measures, digital monitoring and community awareness are crucial to protect vulnerable children.

Methodology

This study used a secondary data analysis approach to review Philippine Supreme Court decisions on cases of online and offline CSEC from 2003 to 2024. The year 2003 was chosen as the starting point as it marks the enactment of the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act (RA 9208), which is the first Philippine law to explicitly criminalise CSEC and establish a legal framework for prosecuting trafficking-related offenses. Using purposive sampling, only those legally adjudicated cases involving monetary or non-monetary exchange were included in order to ensure that the findings are based on definitive legal outcomes. Data were gathered from the Supreme Court e-library, using systematic search terms covering key Philippine laws on child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA). This resulted in 56 cases for final review and inclusion in the study.

A mixed method approach was employed combining quantitative analysis (descriptive statistics on offender profiles, modus operandi and case outcomes), with qualitative thematic analysis to identify patterns and trends in perpetration, enforcement and sentencing. Ethical approval was sought from the University of the Philippines Institutional Review Board and the University of Edinburgh to ensure privacy, data security and researcher well-being. By drawing from comprehensive legal records, this study provides a policy-relevant analysis of how technology has shaped CSEA in the Philippines, with the goal of strengthening child protection efforts in the Philippines.

Key findings

Perpetrators: In the CSEC cases studied, 51% of the perpetrators were women, who often acted as trusted family members or caregivers. Out of 160 identified perpetrators, ‘pimps’ (33%) were the main organisers, with some perpetrators also acting as recruiters (15%). Other offenders, such as hotel owners or karaoke television bar (KTV) operators (8%), provided venues for the exploitation. Some perpetrators were found to have directly abused victims (17%).

Victim-perpetrator relationships: Many perpetrators in the cases were known to their victims. Out of 85 identified relationships between victims and perpetrators, strangers introduced by third parties accounted for 46% of cases, while 17% of cases involved family members, 14% involved friends and 12% neighbours. Recent trends show a rise in younger victims (ages 5 to 12), often exploited by family members or acquaintances in online cases.

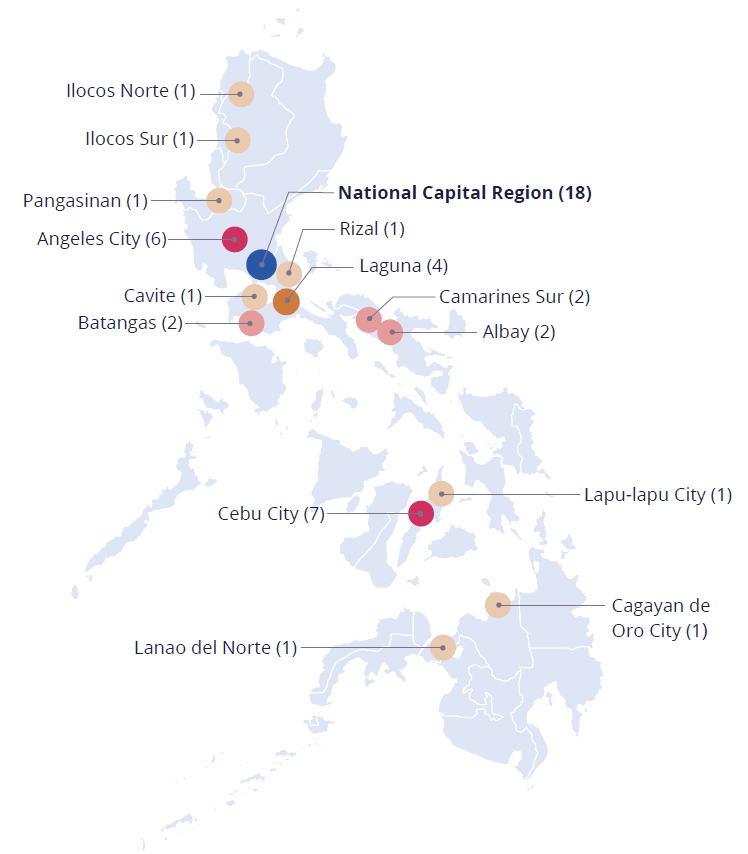

Operations: The majority of CSEC cases studied occurred in urban areas like Manila, Cebu, and Angeles City, where tourism and poverty drive demand for illicit services.

Among the 56 reported cases, 36% involved large-scale operations where three or more children were victimised by one or two perpetrators. Another 27% also involved large-scale operations, but in these cases, the perpetrators were syndicates (i.e., three or more offenders). Meanwhile, 29% of cases involved small-scale operations, where one or two victims were exploited by one or two perpetrators. An additional 9% involved syndicates controlling one or two victims.

Figure 1: Operations scale of commercial child sexual exploitation Supreme Court cases in the Philippines, 2023-24. Number of cases 56

Figure 2: Geographic Mapping of Commercial Child Sexual Exploitation Supreme Court Cases in the Philippines , 2003-2024

Recruitment methods: Common recruitment methods in the cases studied included false job offers (44%), invitations to social gatherings (14%), or direct invitations to engage in ‘prostitution’ (14%). In online cases, coercion, threats, and manipulation (9%) were common tactics.

Figure 3: Methods of recruitment identified in commercial child sexual exploitation Supreme Court cases in the Philippines, 2023-24. Number of cases 128

Financial transactions: The financial transactions in CSEC cases varied. The lowest recorded amount was GBP 0.27 (27 British pence or around 20 Philippine pesos [PHP]), paid directly to a child for sexual contact. The average amount was GBP 134 (9,754 PHP), with the highest recorded payment at GBP 275 (20,017 PHP). Many transactions were facilitated through payment services or cryptocurrency.

Law enforcement and case trends: From 2007 to 2016, CSEC cases were relatively low, with only one to three cases per year. However, from 2017 onward, the number of cases steadily increased, reflecting improved detection and law enforcement efforts. In 2024, 13 cases were reported, 8 of which involved online exploitation. Technology-facilitated cases, like livestreaming abuse, have become more prominent in recent years, with the first livestreaming case brought to the Supreme Court in 2009 .

Figure 4: Supreme Court cases on commercial child sexual exploitation in the Philippines, 2007-2024

Disclosure, reporting, and arrests: Many cases came to attention of authorities through disclosure by children or tips from local and foreign sources. Law enforcement agencies like the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) conduct surveillance and raids to rescue victims and arrest perpetrators. The effectiveness of the legal system relies on collaboration among government agencies, civil society organisations and the private sector. Global collaboration is critical, especially in technology-facilitated cases, where payment and internet service providers are criminally liable under the Philippine Republic Act (RA) 11930 (Anti-OSAEC Law) if they fail to prevent or report illicit transactions and activities linked to online child sexual exploitation. In what is believed to be a first in the East Asia and Pacific region, this landmark legislation expands accountability beyond perpetrators and ensures that the companies enabling these crimes are also held responsible. Before RA 11930, there were already laws like RA 9775 (Anti-Child Pornography Act of 2009) and RA 10175 (Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012) that required internet service providers (ISPs) to block and report abusive content, but these laws did not impose direct criminal liability on financial institutions. In an effort to strengthen child protection in the Philippines, RA 11930 recognises that not just abusers, but also the companies enabling these crimes, must be held responsible in keeping children safe online.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study underscores the changing dynamics of CSEC in the Philippines, with a shift from large-scale operations to smaller, covert groups and an alarming rise in familial exploitation. The increasing use of digital platforms complicates detection and prosecution efforts. While legal frameworks and law enforcement have improved, significant gaps remain, particularly in addressing technology-facilitated crimes and holding all perpetrators accountable.

Key recommendations include:

Recommendation 1. Conduct community awareness programmes. Partner with non-profit organisations to educate the public on identifying and reporting CSEC, particularly in urban centres like Manila, Cebu, and Angeles City. A short, ten-minute video on human trafficking and CSEC should be distributed through schools, workshops, and social media to maximise reach.

Recommendation 2. Establish a case monitoring system. Collaborate with the Department of Justice’s National Coordinating Council Against Online Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children (NCC-OSAEC) to create a digital platform to track CSEC cases in regional trial courts, ensuring transparency and accountability.

Recommendation 3. Put in place a unified hotline system. Consolidate child protection hotlines into a single, easy-to-remember number. Work with telecom companies to integrate these helplines into a digital platform and train volunteers to route calls to appropriate authorities.

Recommendation 4. Develop a unified referral system for online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC). Create a referral pathway that includes government agencies, non-profits, internet service providers (ISPs), and payment providers. This system should enable stakeholders to report suspicious content and transactions through a centralised platform linked to law enforcement.

Recommendation 5. Ensure support from local governments. Encourage local government units (LGUs) to adopt rules to enforce laws against OSAEC and child sexual abuse or exploitation material (CSAEM), including local monitoring teams and prevention campaigns.

Recommendation 6. Equip lawyers and law enforcement authorities with the skills to handle CSEC cases effectively. Provide targeted training for lawyers and law enforcement on handling CSEC cases, using real-life examples and interactive workshops to ensure effective case management.

Recommendation 7. Hold ISPs accountable for responding to child sexual abuse and exploitation content. Develop regulations for ISPs to respond quickly to reports of CSEC content, with a dedicated monitoring body to enforce compliance.

Recommendation 8. Provide victim support services. Increase access to trauma-focused counselling, legal aid, and financial support for victims through coordination with government and non-government organisations.

Recommendation 9. Implement poverty alleviation programmes. Introduce programmes to reduce the vulnerability of families in high-risk communities by providing sustainable livelihoods.

Recommendation 10. Enhance digital surveillance. Equip law enforcement with the tools to monitor online activities and collaborate with ISPs to identify offenders.

These recommendations aim to address both legal enforcement and public health strategies to protect children from exploitation and ensure their safety within their homes and communities.

Limitations

This study is limited by the relatively small number of cases that reach the Supreme Court, especially given the Philippines’ status as a hotspot for livestreamed sexual exploitation and abuse. Supreme Court cases tend to involve more serious, complex incidents, which may not reflect the full range of cases at lower court levels. Additionally, many cases involving plea bargaining do not proceed to the Supreme Court and cases dismissed at lower court levels were not accounted for. As such, the findings may not fully capture the broader scope of CSEC in the Philippines.

Additional information

Suggested citation: Martinez, A., Hernandez, S., Madrid., B., & Fry, D. (2025). Unmasking exploitation: Study of CSEC Supreme Court cases reveals changing landscape of child sexual exploitation and abuse in the Philippines. In: Searchlight 2025 – Childlight's Flagship Report. Edinburgh: Childlight – Global Child Safety Institute

Researchers: Dr Andrea Martinez, Dr Sandra Hernandez, Dr Bernie Madrid and Professor Deborah Fry and students from De La Salle University Law School, Genary Kyna F. Gonzales, Kaori Kato, Airah Danelle M. Tuazon

Study partners: Child Protection Network, Department of Behavioral Sciences, University of the Philippines, Manila and National Institute of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila

Registered study protocol: OSF | A Retrospective Study of the Profiles of Perpetrators of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Cases Decided by the Philippine Supreme Court and University of the Philippines, Manila, Research and Grants Administration Office (RGAO 2024-0766)

Ethics approval: University of the Philippines, Manila, Institutional Review Board (UPM REB 2024-0484-01) and University of Edinburgh, Childlight Research Ethics Sub-Committee (ARSPP-AMA-0240924CL).

Advisory committee members: Hon. Jose C. Reyes, Jr. (retired Associate Justice, Supreme Court of the Philippines and Chair of Philippine Judicial Academy Department of Special Areas of Concern), Dean Maria Concepcion S. Noche (Vice-Chair, Philippine Judicial Academy Department of Special Areas of Concern), Fiscal Lilian Doris S. Alejo (retired Senior State Prosecutor, Republic of the Philippines Department of Justice), Dean Sedfrey M. Candelaria (Chief, Philippine Judicial Academy Research, Publication and Linkages Office), Deputy Regional Prosecutor Barbara Mae Pagdilao-Flores (OIC – Executive Director Republic of the Philippines Department of Justice National Coordination Centre against Online Sexual Abuse and Exploitation and Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Material [NCC-OSAEC-CSAEM])

Funding acknowledgement: The research leading to these results has received funding from the Human Dignity Foundation under the core grant provided to Childlight – Global Child Safety Institute under the grant agreement number [INT21-01].

[1] - Childlight follows the Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse. This favours using the word ‘facilitators’ to describe people who make money from controlling or selling others for sexual services. However, the term ‘pimps’ is used here because it is used in legal contexts and widely referred to in the Philippines.

[2] - Childlight follows the Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse. This favours use of the phrasing ‘exploitation of children in/for prostitution’ rather than ‘child prostitution’ to avoid stigmatising and harming children. However, the term ‘prostitution’ is used here because it is used in legal contexts and widely referred to in the Philippines.