April 2025 / Reading Time: 12 minutes

STUDY F: Legal challenges in tackling AI-generated child sexual abuse material across the UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand: Who is accountable according to the law?

Introduction

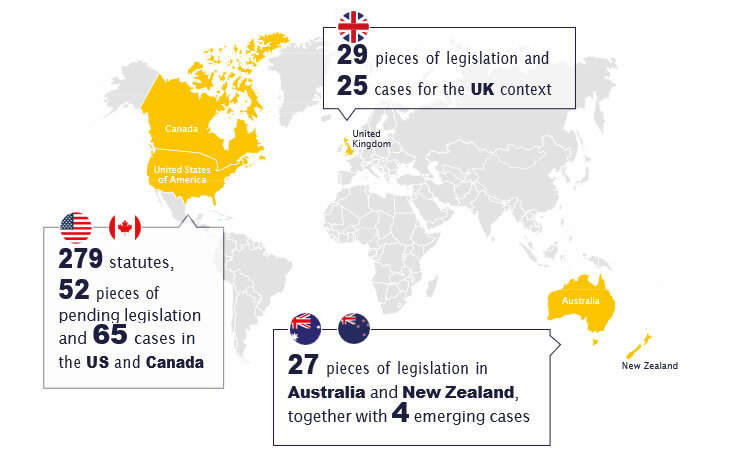

This study is among the first to examine the regulatory context of five closely inter-connected countries (UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) in terms of accountability around child sexual abuse material (CSAM) created via generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI). The findings of our legislative review have helped us identify the key strengths as well as weaknesses of the legislative contexts studied. These countries were selected due to their democratic political systems, technological advances and progressive legislative systems. We examined 29 pieces of legislation and 25 cases for the UK context; 27 pieces of legislation in Australia and New Zealand, together with 4 emerging cases; as well as 279 statutes, 52 pieces of pending legislation and 65 cases in the US and Canada.

Methodology

Legislation and case law in five countries was reviewed and analysed, informed by the ‘black-letter law’ approach, also known as the doctrinal legal research method. This approach focuses on the letter, rather than the spirit, of the law, looking primarily at what the law says and at well-established legal principles, and less at the social context or implications for policymaking.

Figure 1: The number of legislation and cases reviewed for this study

United Kingdom

Findings

Legislation in the UK is divided between reserved and devolved matters. Reserved legislation is adopted by the Westminster Parliament. Devolved legislation is the legislation adopted by the Scottish Parliament or the Northern Ireland Assembly. Both levels of legislation were examined for this study covering all 4 nations of the UK (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales).

The legislation that is relevant for cases of AI-generated CSAM focuses on two types of indecent images. One type is indecent pseudo-photographs, meaning photographs as well as videos and films made by computer graphics that have a photo-realistic appearance, i.e., they look real. The other type covers prohibited pseudo-images that do not look realistic, such as drawings and cartoons or hentai and manga. Manga are Japanese comic books and graphic novels, while hentai are a type of Japanese manga and anime that portrays sexualised content, storylines and characters. There is concern in some parts of the world, such as the UK, that when these types of imagery present children in a pornographic, offensive or otherwise obscene way, focus on children’s private parts or display prohibited acts including children, there is a risk that they may be normalising child abuse and encouraging harmful behaviour. Notably, these concerns are not shared on a global scale and research on the matter is not yet robust.

We found that there is good coverage around a series of offences with regards to pseudo-photographs, i.e., the acts of making, taking, possessing and disseminating pseudo-photographs are all covered, irrespective of the technology used, thus covering cases of generative AI or deepfakes. This is evidenced by the first emerging case in England, where an offender who created CSAM using generative AI was arrested, charged and sentenced to 18 years in prison. In this instance, and as per a recent BBC report, the Crown Prosecution Service, warned that those thinking of using AI “in the worst possible way” should be “aware that the law applies equally to real indecent photographs and AI or computer-generated images of children” (Gawne, 2024). That said, the law is silent on whether the criminalisation of indecent pseudo-photographs of children extends in cases of both real/identifiable and fictitious children.

However, this protection tends to be less efficient with regards to non-realistic images, including cartoons, manga and drawings. While possession and dissemination are criminalised, the act of making such imagery is not criminalised in England and Wales. The largest gap in protection with regards to the above imagery exists in Scotland, as the making and possession of indecent non-realistic images in Scotland is not criminalised. The nation that seems to have the most robust legislative framework against all acts related to indecent non-realistic images is Northern Ireland.

Another gap that exists across the UK is around the possession of paedophile manuals, meaning guides on how to sexually abuse children. Existing legislation does not apply in cases of possessing a paedophile manual that specifically instructs on how to misuse generative AI to produce CSAM. Ongoing UK legal reforms are targeting this specific gap in the legislation (Home Office, 2025). In Scotland, no legislation on paedophile manuals exists whatsoever. Arguably, this may heighten the risk of widespread dissemination of manuals containing instructions on how to sexually abuse and/or exploit children.

There has been no case law, i.e., court cases, on criminal liability for omissions (the failure to perform a legal duty when one can do so) in cases of AI-generated CSAM, but there may be room to argue that it is possible for such liability to arise in the case of a close personal relationship and assumed responsibilities, i.e., in relation to a child’s parent(s) or guardian(s).

Notably, the UK recently adopted the Online Safety Act, which places new duties on social media companies and search service providers to protect children and other vulnerable adult users online. The Act applies specifically to user-to-user services (e.g. social media, photo or video-sharing services, chat services and online or mobile gaming services); search services; and to businesses that publish or display pornographic content (OFCOM, 2025). The regulation of content that is harmful to children is a top priority for the Online Safety Act. Therefore, and among other legislated duties, the law mandates the abovementioned companies to remove illegal content, such as CSAM, and, even if this has been created by generative AI, take steps to prevent users from encountering it (OFCOM, 2024).

From a civil perspective, there is no specific legislation or case law in the UK that directly addresses this issue, leaving a significant gap. However, AI-generated CSAM seems to fall under the protective remit of the Data Protection Act 2018.

There is the ability to claim compensation in the UK with regards to CSAM created via gen-AI technologies that includes figures modelled after real, identifiable children via a number of pathways (a civil claim, privacy infringement, compensation order via criminal courts, and, much less likely, via the Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme [CICA]). However, the liability for AI-CSAM, i.e., the question ‘who is the author of AI’, remains currently unclear under existing legislation across the UK.

What also became evident from the above analysis is the fact that the UK lacks a targeted AI industry regulation, like the one that was recently adopted in the European Union in the form of the EU’s AI Act. There seem to be no plans at the moment for a standalone UK AI Act.

Lastly, a more recent legal reform concerns AI tools. More specifically, the UK is considering making it illegal to possess, create or distribute AI tools designed to create CSAM, with a punishment of up to five years in prison (Home Office, 2025).

Recommendations

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are made for the UK:

Recommendation 1. Update the law to clearly criminalise all acts relevant to pseudo-photographs that depict purely fictitious children, i.e., making, taking, disseminating and possessing such material.

Recommendation 2. The Scottish Government should introduce legislation to criminalise all acts relevant to non-photographic indecent images of children, i.e., making, taking, disseminating and possessing such material.

Recommendation 3. Criminalise the making of prohibited non-photographic images of children.

Recommendation 4. Update UK legislation on paedophile manuals to make it applicable on pseudo-photographs. As stated above, reforms on the matter are currently underway.

Recommendation 5. Introduce Scottish legislation criminalising paedophile manuals.

Australia and New Zealand

Findings

With regards to Australia, the same issues were examined on both a national as well as a state and territory level, whereas in New Zealand they were examined only on the national level, as no relevant legislation exists on a devolved basis. It is worth considering that Australia also enacted an Online Safety Act (OSA) in 2021, which imposes certain duties on online service providers with regard to protecting Australians, in particular children and vulnerable adult users online.

The eSafety Commissioner was established in 2015 (then the ‘Office of the Children’s eSafety Commissioner’) in Australia and serves as an independent regulator for online safety, with powers to require the removal of unlawful and seriously harmful material, implement systemic regulatory schemes and educate people around online safety risks. Under the OSA, there are currently enforceable codes and standards in force which apply to AI-generated CSAM with civil penalties for services that fail to comply. In particular the ‘Designated Internet Service’ Standard applies to generative AI services, as well as model distribution services.

The OSA was independently reviewed in 2024. The Review examined the operation and effectiveness of the Act and considered whether additional protections are needed to combat online harms, including those posed by emerging technologies (Minister for Communications, 2025). The Final Report of the review was tabled in Parliament in February 2025.

The Australian Government has also recently conducted consultations regarding the introduction of mandatory guardrails for AI in high-risk settings, which considers guardrails like ensuring that generative AI training data does not contain CSAM (Australian Government, Department of Industry, Science & Resources, 2024). No such legislation exists in New Zealand, although there are ongoing discussions and legal reform suggestions around the potential introduction of similar legislation there.

In both Australia and New Zealand, existing definitions of CSAM or similar terminology used in criminal legislation are broad enough to capture AI-generated CSAM. As a result, and despite limited case law on the matter due to the emerging character of gen-AI technologies, sentencing decisions have emerged in the Australian states of Victoria and Tasmania involving offenders who produced gen-AI CSAM.

In New Zealand, no cases have yet been identified in which offenders have been sentenced for offences involving AI-generated CSAM, however, press reports suggest that offenders have been charged in relation to such material. In addition, there are reports of the New Zealand customs service seizing gen-AI CSAM, suggesting that they consider that they have the jurisdiction to do so. No cases have been identified in Australia or New Zealand in which AI software creators or holders of datasets used to train AI have been considered criminally liable in relation to the production of CSAM using their platforms or any other such charges.

In New Zealand, certain pieces of legislation (e.g., Crimes Act 1961 and Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015) do not appear to apply in cases of gen-AI CSAM that portrays purely fictitious children. This is to an extent expected, as both laws require harm to be inflicted upon an identifiable natural person and this is not the case in instances of AI-generated CSAM containing purely fictitious children.

In both Australia and New Zealand, there are no pending reforms to expand criminal accountability in relation to gen-AI CSAM to AI software creators and dataset holders. Given that the definitions of CSAM in existing criminal legislation appear broad enough to capture AI-generated material, this is not surprising.

Recommendations

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are made for Australia and New Zealand:

Recommendation 1. Monitor the applicability of relevant legislation (particularly of the Australian Online Safety Act) as was recently done by the review of the OSA and the Australian Government’s intention to introduce a digital duty of care, and review emerging case law to further assess applicability.

Recommendation 2. Policymakers and legislators need to thoroughly assess whether civil penalty provisions should be further increased in Australia and New Zealand, in line with other jurisdictions internationally.

Recommendation 3. Policymakers and legislators need to thoroughly assess whether existing regulations cover criminal liability for AI software creators or dataset holders who failed to install proper guardrails in their products that would safeguard children before rolling them out in the market. We found no specific legislation on this. Case law interpretation on this is also crucial. These topics also relate to questions around who the author of AI is and if the law should delineate a minimum standard of guardrails that need to be met by AI creators, beyond which they have no liability.

United States of America and Canada

Findings for USA

In the United States of America, the regulatory framework consists of federal laws and state-based laws. Federal CSAM statutes, together with case law, criminalise several categories of harmful material. Still, a significant number of vague points persist. Federal laws are relatively robust, but there is a gap with regards to the criminalisation of artificial CSAM that depicts purely fictitious children. Civil remedies, although significant, are limited in scope. Copyright and consumer protection laws offer some avenues for redress, but they are also limited.

Prosecutors typically require concrete evidence to prosecute, such as incriminating communication or attempts to sell or trade material. These are often hard to obtain. This challenge is increased by more advanced AI models that generate hyper-realistic CSAM without training on authentic abuse imagery. This means that even if we start regulating how AI models are trained, these advanced AI models that can create realistic CSAM without the need for training will be evading regulation.

Drawing on copyright law, platforms and developers can be held liable if they knowingly contribute to the sharing of harmful content. However, online platforms are protected from civil liability for user-generated content, complicating efforts to hold them accountable for hosting AI-generated CSAM. Despite efforts to change the law on this, balancing platform liability with the protection of free speech is a major challenge.

The legal landscape is even more fragmented on a state level due to several outdated pieces of legislation around so-called ‘child pornography’ [1], which fail to address newer forms of technology-facilitated child sexual abuse. State-level civil remedies are often inadequate, leaving gaps in accountability for users, developers, distributors and third-party beneficiaries.

On 16 April 2024, the Child Exploitation and Artificial Intelligence Expert Commission Act of 2024 was introduced to address the creation of CSAM using AI. This legislation provides for the establishment of a commission to develop a legal framework that will assist law enforcement in preventing, detecting and prosecuting AI-generated crimes against children.

Findings for Canada

In Canada, there is a distinction between federal law and province-based law. The federal Criminal Code lacks specific prohibitions against AI-generated CSAM. Still, the relevant sections of the Canadian Criminal Code have been interpreted widely by the Supreme Court of Canada to provide coverage for several types of harmful material. There remain two exceptions, though. The first is for material that has been created only for personal use and the second is for works of art that lack intent to exploit children. Canadian federal law criminalises the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. However, whether these provisions apply to AI-generated CSAM is uncertain. Enforcement is the responsibility of provincial agencies, and civil remedies for victims vary widely across provinces, creating a patchwork of protections in which access to relief depends on the victim’s location.

Privacy laws in Canada offer some avenues for assistance, but they lack a more tailored character to address the specific harms associated with AI-generated CSAM. Copyright law offers a potential, although complex, avenue for addressing AI-generated CSAM.

Lastly, in Canada, a significant law reform that was proposed is the Online Harms Act. If passed, this Act will create a new regulatory framework requiring online platforms to act responsibly to prevent and mitigate the risk of harm to children on their platforms. Under the Act, online platforms would have a duty to implement age-appropriate design features and to make content that sexually victimises a child or re-victimises a survivor inaccessible, including via the use of technology, to prevent CSAM from being uploaded in the first instance. A new Digital Safety Commission would oversee compliance and be charged with the authority to penalise online platforms that fail to act responsibly.

Accordingly, the Act would create a legally binding framework for safe and responsible AI development and deployment that could potentially apply to restrict or penalise content that would otherwise be legal, but that poses a substantial risk of sexual exploitation or revictimisation of a child. Prorogation of the Parliament of Canada ends the current parliamentary session. As a result, all proceedings before Parliament end, and bills that have not received Royal Assent are ‘entirely terminated‘. This means that the Online Harms Act would need to be reintroduced by the new government in Canada before it could be considered again for Royal Assent (Lexology, 2025).

Recommendations

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are made for the USA and Canada:

Recommendation 1. Amend existing CSAM laws to explicitly cover AI-generated content, even when it includes fictitious children.

Recommendation 2. Amend CSAM laws to regulate the misuse of AI.

Recommendation 3. Amend CSAM laws to cover content that is legal, but poses a substantial risk of harm to minors (e.g., grooming or nudity content).

Recommendation 4. Establish a legally binding framework for safe and responsible AI development and deployment.

Recommendation 5. Expand legal protections to include control over one’s own image.

Limitations

The main limitation of this research stems from the emerging character of the technology it considers. This applies particularly to case law and the interpretation of existing legislation by courts, because, due to the developing character of this technology, we still have not seen robust case law established in relation to AI and deepfake CSAM that would create strong precedents. As such, this research should be replicated in 5 to 10 years' time, when there is more robust case law on the matter.

More information

Suggested citation: Gaitis, K.K., Fakonti, C., Lonard, Z., Lu, M., Schidlow, J., Stevenson, J., & Fry, D. (2025). Legal challenges in tackling AI-generated child sexual abuse material across the UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand: Who is accountable according to the law? In: Searchlight 2025 – Childlight's Flagship Report. Edinburgh: Childlight – Global Child Safety Institute

Researchers: Dr Konstantinos Kosmas Gaitis, Dr Chrystala Fakonti, Ms Zoe Lonard, Dr Mengyao Lu, Ms Jessica Schidlow, Mr James Stevenson, Professor Deborah Fry

Study partners: Child USA, Norton Rose Fulbright Australia

Registered study protocol: OSF Registries| Accountability within legislation on AI-generated CSAM

Ethics approval: University of Edinburgh, Childlight Research Ethics Sub-Committee (DELOC-KKG-0030424CL)

Advisory committee members: Professor Ben Mathews (School of Law, Queensland University of Technology), Dan Sexton (Chief Technology Officer, Internet Watch Foundation), Michael Skwarek (Manager, Codes and Standards Class 1, Industry Compliance and Enforcement, Australian eSafety Commissioner)

Funding acknowledgement: The research leading to these results has received funding from the Human Dignity Foundation under the core grant provided to Childlight – Global Child Safety Institute under the grant agreement number [INT21-01].

[1] - Childlight follows the Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse. The terms ‘child abuse’, ‘child prostitution’, ‘child pornography’ and ‘rape’ are used in legal contexts.